A Day's Catch Winnebago County, WI | How to Ice Fish for Walleye

They never cease to amaze. Not walleyes, but the walleye anglers who desperately seek to pigeonhole their favorite fish. The folks who want hard and fast rules. Who long to see the walleye world in black and white when, in fact, it exists in shades of gray. Especially under ice.

Doesn't mean you can't figure out walleye movements at first-, middle-, and last-ice. Not if you remember that what influences walleye activity on a small lake in Minnesota is vastly different from what makes walleyes tick on the Bay of Quinte off Lake Ontario. Those differences will affect how, when, and where you find walleyes moving under the ice. Indeed, we can ice fish on so many different lakes, rivers, reservoirs, pits, and ponds these days, in so many different parts of the continent, that the only constant often is the walleye itself.

The Migratory Myth

We refine our understanding of winter walleye movements by dispelling the myth about walleyes being nomadic—always on the move—and prone to long-distance migrations. This is true for some lakes and reservoirs at some times of the year, but as a rule, in winter, it's an oversimplification. Most walleye movements ice fishermen worry about aren't winter movements at all.

Perhaps the myth started with mark and recapture studies, like the one on Lake Champlain, that showed more than 60 percent of walleyes in the north end migrating over 30 miles downriver to the St. Lawrence. Another study, on Lake Winnebago, showed 21 percent of the tagged adult walleyes recaptured 25 to 90 miles away from their release point. Other studies have pegged walleye movements at 120, 160, and as many as 240 miles.

Most of this research, though, was conducted on large lakes and reservoirs. Furthermore, it was associated with prespawn and postspawn movements. Those walleyes swam long distances to reach suitable spawning grounds, or returned to their open-water summer haunts after spawning. Little tracking was associated with winter movements. Actually, it's because some walleyes in some lakes make long-distance migrations prior to ice-up, that we enjoy some of the best and most stable ice action.

Many biologists and fishery researchers suspect that these big-water walleyes time long-distance autumn moves to the vicinity of their spawning grounds, to take advantage of their peak physical condition. Better to make the journey in fall after a summer life of leisure than in spring when winter-weary egg-laden females would be stressed by the exercise. Winter fisheries around the west end of Lake Erie, the Bay of Quinte, and the Red River in Manitoba are examples. In each case, large groups of walleyes migrate long distances in fall, to settle and bunch for winter, close to where they spawn in March, April, or May.

The ice-fishing season is predominantly a period of relative stability, characterized in most walleye waters by minimal long-distance movements. Even when these movements do occur, as on Erie, Quinte, and the Red River, they usually represent the last leg of an open-water fall migration. The continued trickle of walleyes in these lakes and rivers benefits the fishing action.

Short Horizons

Because of cold water temperatures and slower metabolic rates, walleyes move less than during summer. When they do move horizontally from one structure to another, the range generally is confined, the pace usually measured and slow, and the moves most often based on forage shifts and fishing pressure.

But horizontal moves often don't happen at all. That's why, at first-ice, the best places to locate walleye (as we've detailed many times in the past) usually are the most classic walleye structures on the lake, precisely where you left the fish in fall. It's also why on large multi-structured lakes when fishing pressure is light, you can routinely sit on one group of walleyes (or several groups trading between structures) in one general area for much of the winter.

Pointers

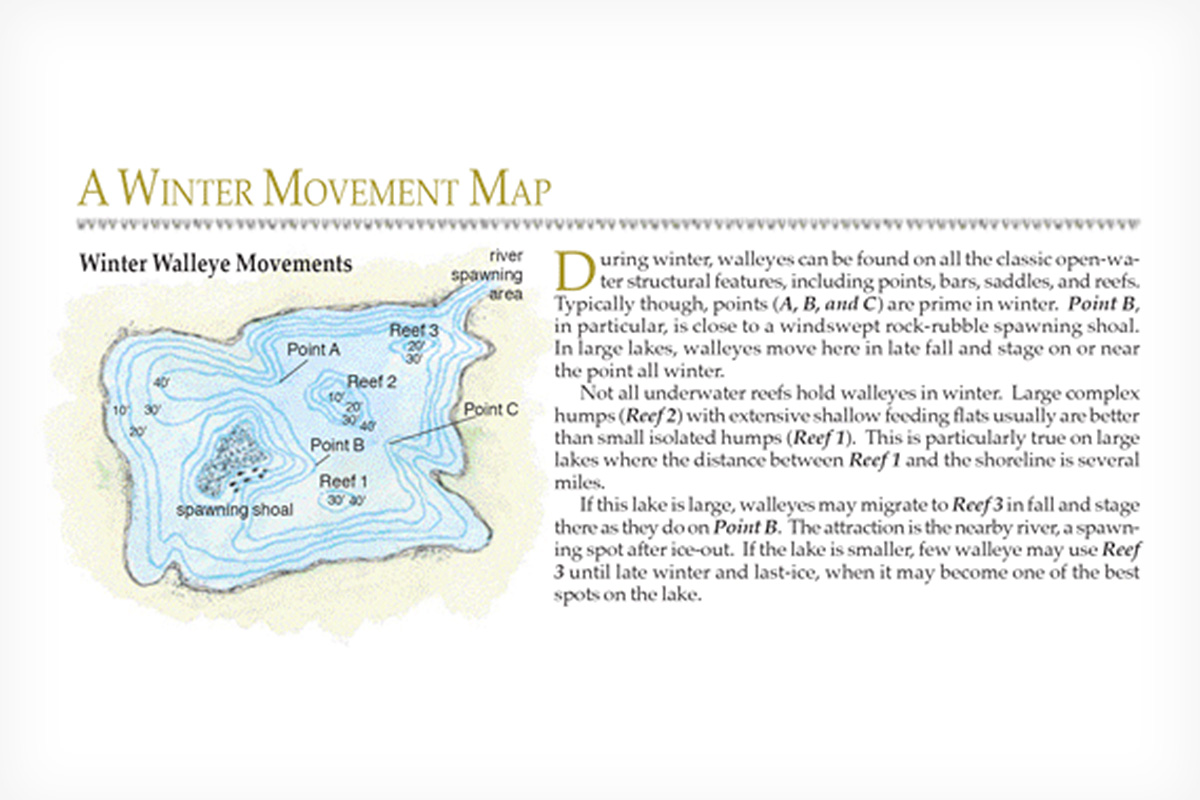

One of the most important things I've noted in 45 years of walleye fishing is that island and mainland points are supreme spots under ice. Not that fish won't also hold on reefs, bars, humps, and saddles. A good point, though, is routinely better in winter.

I suspect that what's happening is a miniaturization of what we see on big lakes like Erie, Ontario, and Huron, where walleyes make late fall treks toward spring spawning areas. On smaller inland walleye waters, the same, albeit much more subtle, movements occur. This is why a rock and rubble mainland or island shoreline spawning shoal holds walleyes nearby on points all winter.

Moving Up In The Walleye World

While walleyes may have most of the long-distance wanderlust out of their systems by the time we start drilling holes in November, December, and January, that doesn't mean they stop moving. Now, though, the movement is vertical—from deep to shallow and back down again. An empty belly and light levels trigger these shifts.

Walleyes are largely piscivorous (fish eaters). They take lake shiners, trout perch, sticklebacks, alewives, and suckers. But perch, lake herring (tulibee or cisco), and smelt usually top the dining menu.

When those forage fish are shallow, walleyes move shallow to eat them. When forage is deeper, walleyes move deeper. When forage is on the move, walleye are mobile, too, although often they position on structural elements to intercept passing prey. This positioning usually is along moderate- to sharp-breaking edges, as opposed to atop shallow flats. Either way, find forage and you find walleyes.

This concept of energy expenditure has been documented for every gamefish species, from smallmouths to muskies to walleyes. When schools of perch, tulibee, or shiners are thick on a structure, walleyes usually won't move elsewhere. When forage is scarce or migratory, walleyes out of necessity become more mobile.

Winter throws a twist into the equation, however. In spring, after spawning, a walleye daily consumes one percent of its body weight in food. During the pre-summer peak, that rate doubles. In summer, when water temperatures are ideal, a walleye's metabolic rate is racing and peaks at three percent or more. But in late fall and winter, when water temperatures drop below 54°F, walleyes enter a stage of maintenance feeding. They eat only enough to keep their internal furnaces burning.

The Big Turn-On

When walleyes feed in the wintertime is another factor that affects their daily movement and activity patterns. We've documented the pioneering work of Dr. Dick Ryder of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Dr. Dwight Burkhardt of the University of Minnesota. Burkhardt revealed how highly sensitive a walleye's eyes are to light. Ryder documented how light affects walleye movements, suggesting that feeding activity is triggered most often by changing light levels.

Even though light levels under the ice are only about 10 percent of summer levels, Ryder found no seasonal differences or changes in walleye feeding and movement patterns. The fish react in December and January as they do in July or August. Absolute light levels aren't critical factors. The switch that stirs walleyes into moving and feeding, regardless of the season, is the rate of change of light intensity. Specifically, the periods are 90 minutes surrounding sunrise and the 90 minutes around sunset. Ryder also found that walleyes move and feed more heavily during the evening transition than during the morning transition.

Contour Ice Fishing

Top anglers have witnessed this fantastic flurry of winter walleye activity so many times that they've developed a to-do list to take advantage of it. They set up on a classic structure by late midday and pre-drill plenty of holes to cover potential deep, mid-depth, and shallow feeding spots. It's the winter

Often, the first wave of walleye activity occurs in the deeper holes. Eventually, a flag will fly or someone will jig up a walleye in one of the moderately deep holes. Those holes may continue to produce fish for 10 or 15 minutes. Then someone hauls up a walleye from a shallow set. The rush is to jig atop the structure. Prepared anglers follow the wave of walleyes up and over a structure until pitch dark and it's time to go home.

This flurry of activity at sundown is super-charged in December and January. Because of the short days, given the position of prime walleye ice-fishing country relative to the sun, the heavy schooling activity of the fish, and the limited maintenance-feeding habits of walleyes in winter, typically you'll enjoy 20 to 30 minutes of delightful madness before the action calms down.

In March and April, on the other hand, the days are longer, the frozen North Country is tilted closer to the sun, and while the walleyes still are on a Jenny Craig-like diet program, activity is increasing. Do walleyes feed more heavily as they get ready to spawn? Do energy demands increase in order to mature ripening eggs? Are walleyes milling about in preparation for a last-ditch hike to spawning shoals? Or are they reacting to increasing photo periods?

Probably all of these, which is why the 30-minute flurry of intensity at first-ice typically triples to a 90-minute period at last-ice. No better way to end the winter walleye season.